On Monday morning I awoke early, walked the dog, and got myself ready for the first day back to work. I grabbed a jacket on my way out the door and reluctantly covered my rapidly-fading tan.

In the subway it struck me with unwelcome force that summer was fully over. SLAM!

On my left I spied leather boots and tweed. On my right: scarves as far as the eye could see. The billboards were peddling their back-to-school wares and I had a strange hankering for root vegetables.

La rentrée, dear friends, is in full effect. And the effect is substantial, as are the vacations from which the French are returning.

“Vacation?”

The brows of my American readers are pinched. Let me explain:

Vacation [vey-key-shuhn] - noun

A period of suspension of work, study, or other activity, usually used for rest, recreation, or travel.

“Whah?...”

I know: it’s a difficult concept. French workers (those with a real contract, anyway) are entitled annually to five weeks paid vacation. In practice, however, the French take closer to seven paid weeks every year.

“But that’s almost two months!”

This figure is almost impossible to understand for Americans who, at all levels of employment, have a very different orientation to time off.

Nearly a quarter of American workers, particularly those in part-time or temporary jobs, are not offered any paid vacation. I spent many years waiting tables, during which time I was obliged to locate a replacement for every day of (uncompensated) “missed” work. If I couldn’t find a replacement, I couldn’t go. Vacations, as a result, entailed economic hardship and were limited to summer weddings and a few days around Christmas.

When paid vacation is offered, it’s usually a pittance and dependent on the number of years employed by a company. Because American workers change jobs more often than their European counterparts, their vacation eligibility is kept relatively low. Nine days per year is the average for workers with one year at a company. What’s more: these precious days are often “spent” by workers with health problems or care-giving responsibilities after their small allotment of “personal” and “sick” days has been used up.

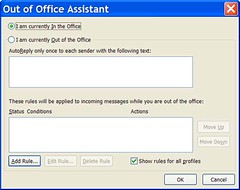

Finally, there is a class of American worker who, despite a more generous benefits package, chooses not to take vacation. A recent survey showed that among workers who are entitled to paid vacation, 36% were not planning to use all of it. These are the people who “do not have the time” for a vacation, who feel their whole professional universe will crumble when they leave their desk. Often these unspent vacation days are translated into a monetary pay-out at the end of the year or when the worker changes jobs.

French workers and their families leave town for three weeks minimum in late July and August. The obvious result is that businesses are closed or operating with minimal staffing during this time. The workers may be traveling or spending time at the family country home - the important thing is that they are not working.

As a result (or perhaps cause?) of this time away, the French tend to be much less work-oriented than Americans. At a French dinner party you will not be asked about your profession. At least not until after the more-interesting topics (including your last vacation) have been exhausted. By contrast, I often found myself in Boston wishing I’d brought a stack of resumes to hand out at social events. “Where do you work? What degrees to you have? From where?...”

My Boston salary, it should be said, was more than double what I now earn. And thus we stumble upon the main argument against French vacation: that it just costs too much.

But is that true? And moreover, so what?

My salary, while low by American standards, is sufficient for my life in Paris. This is helped by the fact that I don’t have to pay hundreds of dollars every month for health insurance, car insurance, car loan, and gas. If I didn’t have student loans, which the French don’t, I’d be living even higher on the chestnut-fed hog. Same goes for “if I owned my own apartment,” which many Parisians do.

To experience serious salary increase, the French would have to barter away the things that make their lives better. And the overwhelming majority of them are unwilling to trade this for the contestable glory of consumer living.

So they sit, well-tanned and talkative, on the first-Monday Métro. Smiling contentedly that they still have something from which to return.